Notes on Solidity

The Ethereum Smart Contract languaje.

by oschvr

Solidity is a contract-oriented, high-level language whose syntax is similar to that of JavaScript and it is designed to target the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM).

Based on the documentation provided by the Ethereum Foundation, the Solidity programming languaje provides the tools to create Smart Contracts that interact with the Ethereum Blockchain.

I will cover the following topics:

- Smart Contracts

- Blockchain Basics

- Ethereum Virtual Machine

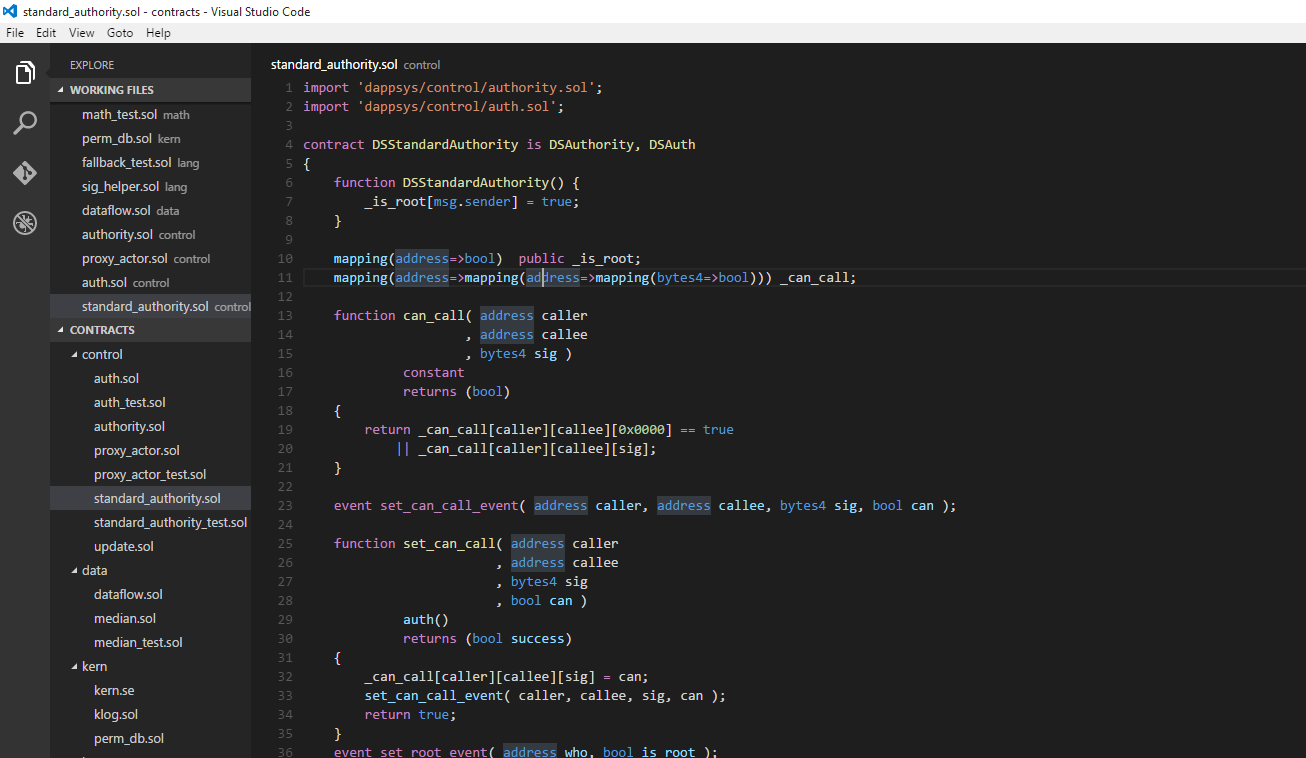

I’m using VS Code for MacOS, here’s an example of how it looks, with the extension by Juan Blanco:

+++

Smart Contracts

A contract, in the sense of Solidity, is a collection of code (it’s functions) and data (it’s state) that resides at a specific address on the Ethereum blockchain.

An very basic example of a smart contract is as follows:

Storage Example

pragma solidity ^0.4.0;

contract SimpleStorage {

uint storedData;

function set(uint x) {

storedData = x;

}

function get() constant returns (uint) {

return storedData;

}

}

pragmasimply tells the version of Solidity.uint storedData;declares a state variable calledstoredDataof typeuint(unsigned integer of 256 bits).setandgetare the functions that are used to modify or retreive the value of the variable.

Note: To access a state variable, you do not need to declare the prefix this as it is common in languages like Javascript.

Let’s look at another example, where the contract will implement the simples form of a cryptocurrency.

Subcurrency Example

pragma solidity ^0.4.0;

contract Coin {

// The keyword "public" makes those variables

// readable from outside.

address public minter;

mapping (address => uint) public balances;

// Events allow light clients to react on

// changes efficiently.

event Sent(address from, address to, uint amount);

// This is the constructor whose code is

// run only when the contract is created.

function Coin() {

minter = msg.sender;

}

function mint(address receiver, uint amount) {

if (msg.sender != minter) return;

balances[receiver] += amount;

}

function send(address receiver, uint amount) {

if (balances[msg.sender] < amount) return;

balances[msg.sender] -= amount;

balances[receiver] += amount;

Sent(msg.sender, receiver, amount);

}

}

address public minter;declares a state variable of type address that is publicly accessible.addresstype is a 160-bit value that doesn’t allow arithmetic operations. Only suitable for storing addresses of contracts or keypairs belonging to external persons.publicautomatically generates a function that allows you to access the current value of the state variable. This is how that function looks:

function minter() returns(address) {return minter;}

mapping(addres => uint) public balances;also creates a public state variable. The type maps, addresses to unsigned integers. Mappings can be seen as hash tables which are virtually initialized such that every possible key exists and is mapped to a value whose byte-representation is all zeros. The getter function created by thepublickeyword looks like this:

function balances(address _account) returns (uint) {

return balances[_account];

}

event Sent(address from, address to, uint amount);declares a so-called “event” which is fired in the last line of the functionsend. UIs can listen to those events being fired on the blockchain. As soon as fired, the listener will also recieve the argumentsfrom,toandamount. To listen to the events, you would use:

Coin.Sent().watch({}, "", function (error, result) {

if (!error) {

console.log(

"Coin transfer: " +

result.args.amount +

" coins were sent from " +

result.args.from +

" to " +

result.args.to +

"."

);

console.log(

"Balances now:\n" +

"Sender: " +

Coin.balances.call(result.args.from) +

"Receiver: " +

Coin.balances.call(result.args.to)

);

}

});

The special function

Coinis the constructor which is run during the creation of the contract. Cannot be called afterwards. It permanently stores the address of the creator:msg(together withtxandblock) is a global variable that contains properties which allow access to the blockchain.msg.senderis always the address where the current (external) function call came from.The functions

mintandsendare the ones that end up with the contract and can be called by users and other contracts. Ifmintis called by anyone but the creator, nothing will happen. On the other hand,sendcan be called by anyone (that already has some of these coins) to send coins to anyone else.

Blockchain Basics

Although there are some complex concepts that underlay and exist to provide a set of features and promises (hashing,elliptic-curve cryptography,mining,p2p networks), we accept them as given and not worry further to create smart contracts. There are only to concepts to understant in a very basic sense:

Transactions

A blockchain is a globally shared, transactional database. If you want to change something in the database, you have to create a so-called transaction which has to be accepted by all others.

Blocks

An order of the transactions will be selected for you, the transactions will be bundled into what is called a “block” and then they will be executed and distributed among all participating nodes.

Ethereum Virtual Machine

The Ethereum Virtual Machine or EVM is the runtime environment for smart contracts in Ethereum.

The EVM is not only sandboxed, but completely isola ted. This means that the code running inside the EVM has no access to network, filesystems or other processes.

Accounts

There are two kinds of accounts in Ethereum, External accounts, controlled by public-private keypairs (i.e. humans), and contract accounts, controlled by the code stored together with the account.

These two are treated equally on the EVM

Every account has a persistent key-value store mapping 256-bit words to 256-bit words called storage.

Every account has a balance in Ether (in “Wei” to be exact).

Transactions

A transaction is a message sent from one account to another. It can include binary data (its payload) and Ether.

If the target account contains a contract, the code is executed using the paylod provided as input data.

If the target account is the zero-account (account with address 0), the transaction creates a new contract.

Gas

Upon creation, each transaction is charged with a certain amount of gas, whose purpose is to limit the amount of work needed to execute the transaction and to pay for this execution. While the EVM executes the transaction, the gas is gradually depleted.

The gas price is a value set by the creator of the transaction, who has to pay gas_price * gas up front formo the sending account. If some gas is left after the execution, it is refunded in the same way.

If the gas is used up at any point, an out-of-gas exception is triggered, which reverts all modifications made to the state in the current call frame.

Storage, Memory and the Stack

Each account has persistent memory which is called storage, a key-value store mapping 256-bit words to 256-bit words. It’s costly to read and even more so, to modify storage. A contract cannot read nor write to any storage.

The second memory area is called memory, of which a contract obtains a freshly cleared instance for each message call. Reads are limited to a width of 256bits, while writes can be either 8bits or 256 bits wide. Memory is expanded by a word(256-bit), when accessing a previously untouched memory word. At the time of expansion, the cost in gas must be paid. Memory is more costly the larger it grows (it scales quadratically).

The EVM is not a register but a stack machine, so all computations are performed on an are called stack. Max size of 1024 elements and contains words of 256 bits.

Instruction Set

The instruction set in the EVM is kept minimal in ordrer to avoid incorrect implementations that can cause consensus problems. All instructions operate on a 256-bit word basis. Arithmetic, bit, logical and comparison operations are present. Conditional and unconditional jumps are possible.

Message Calls

Message calls are similar to transactions, in that they. hace source, target, data payload, Ether, gas and return data.

The called contract will recieve a freshly cleared instance of memory and has access to the call payload, provided in an area called calldata

Calls are limited to a depth of 1024, which means that for more complex operations, loops are preferred over recursive calls.

Delegatecall / Callcode and Libraries

A delegatecall is a variant of a message call, identically structured, but that doesnt change the values.

Logs

A specially indexed data structure that maps all the way up to the block, that can be possibly stored, is called logs.

Create

Contracts can create other contracts ising a special opcode. The difference with a normal message call is that the payload is executed and the result stored as code and the caller/creator recieves the address of the new contract.

Self-destruct

The only way that code is removed from the blockchain is when the contract calls selfdestruct operation.